Nobel prize laureate Muhammad Yunus was sworn in as prime minister of Bangladesh last week after being offered the role by student protesters whose months-long campaign led to the fall of the government of former prime minister Sheikh Hasina. In Bangladesh, it is the start of a new chapter. We take a look at how this unprecedented student movement organised online to raise awareness worldwide about what was happening on the ground.

When Nobel prize laureate Muhammad Yunus arrived on Bangladeshi soil on August 8, it marked a new political era for the country. Yunus was sworn in as prime minister of Bangladesh after being offered the role by student protesters, who had defied brutal crackdowns to take to the streets for over a month.

The group at the heart of the movement is called the “Students Against Discrimination” and it was created by students who didn’t want a part in pre-existing political parties. Though they were initially protesting quota reform, their movement quickly snowballed, culminating in the fall of the government controlled by the Awami League and then prime minister Sheikh Hasina, who had been in her post for more than 15 years.

The student movement organised giant protests but, beyond that, they also carried out mass online campaigns to raise awareness, which led to an unprecedented mobilisation. Our team wanted to learn the ins and outs of how this campaign was organised and spoke to students both in Bangladesh and abroad to find out more.

‘We divided up the work’

Protests continued over the past month, even though the Bangladeshi government regularly cut the country’s internet connection, sometimes for several days at a time.

The students began to work so that the world would know about what was happening in Bangladesh. While some students were out in the streets protesting, others established a large-scale media campaign.

First of all, they needed to make sure that photos and videos documenting the violent repression of protests were accessible outside of social media platforms, which are also subject to regular censure.

“Agontuk”, an engineering student in Dacca, the capital of Bangladesh, told us more about this student-led media campaign (Like the other Bangladeshi students interviewed by our team, he asked to remain anonymous for fear that the repression that took place during these protests might continue even with a transition government in place.)

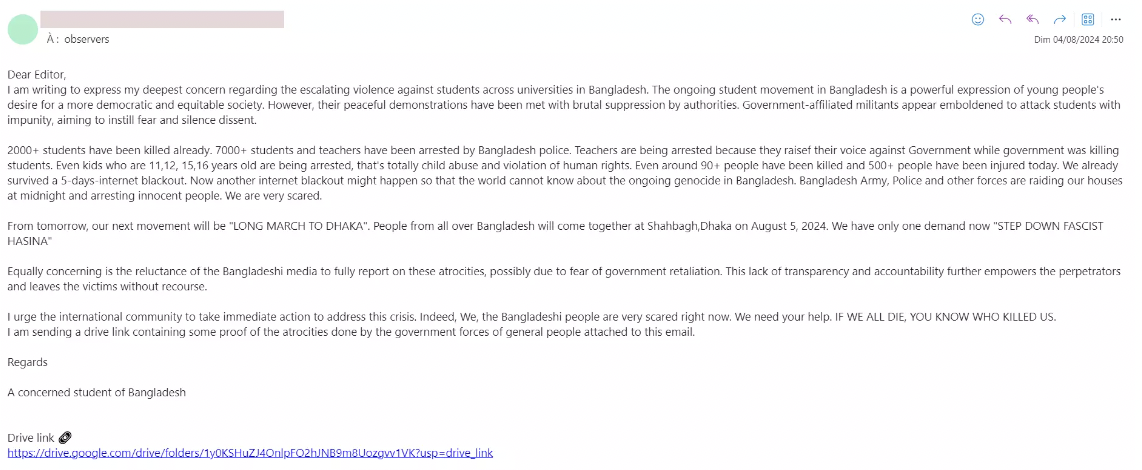

We gathered images posted on the X accounts of Bangladeshi human rights activists, but we also got some images from videos posted on YouTube and Facebook lives. Our aim was to get these images to international media outlets and institutions like the International Criminal Court.

We rarely knew when the government would allow us to access the internet again. We were afraid that they would delete information on social media so we decided to store them on Google Drive and in our telephones.

This meticulous gathering of evidence was largely led by students and was a way for students who couldn’t join the protests to participate in the movement.

The work on the ground enabled our online campaign to organise. We wouldn’t have been able to do anything if the majority of students hadn’t taken to the streets. Those of us who couldn’t take to the streets organised online.

We created a group at my university to discuss strategy. How should we contact international media outlets? What should we say? We gathered the email addresses of media outlets like France 24, the BBC, Al Jazeera and then we divided up the work.

Help from abroad

Syed Rahber, who lives in France, was one of the young Bangladeshis living abroad who took part in the student movement. Students living abroad took the lead when it became too dangerous for those in Bangladesh to speak out online.

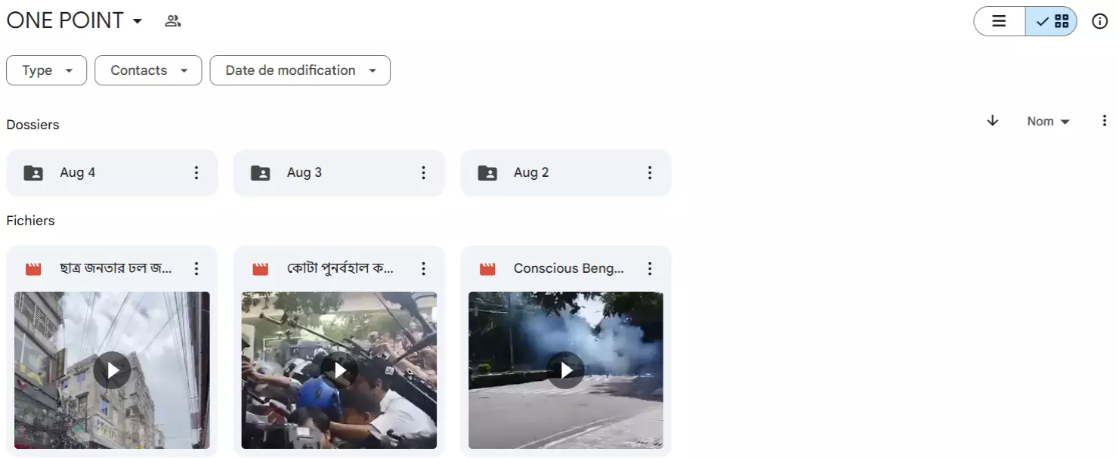

“My aim was to raise awareness about what was going on with as many people as possible as well as international media outlets. I created these folders on Google Drive so that we could save evidence of crimes committed, in case there are trials in the future. Because the media and government [in Bangladesh] are corrupt.”

This was the first time that Syed, who is only 17, became involved in a political cause.

“I was not political before. In my country, it is almost impossible to publicly criticise the government. We would talk about it among friends, never in writing, but we would never really organise into an activist movement. In Bangladesh, it is hard for young people to become political, there is retaliation from the government. Unless you are in a student league, but that’s not anything me or my friends do because these leagues cause pain around them.

Breaking from so-called student leagues

Student life in Bangladesh is controlled by so-called student leagues, which are the university branches of political parties. There are three main ones, which correspond to the three major political parties in the country. They have a considerable influence on student life: they control access to online courses, manuels and even access to student accommodation or a job. Being part of a league is a real social elevator for people in Bangladesh.

New politicisation of the youth

Breaking free from these student leagues, the “Students Against Discrimination” movement gave hope to the young Bangladeshi diaspora. While Rahber began documenting the protests independently, he began slowly to connect with other people from the Bangladeshi diaspora living in other countries. Together, they formed a group called “Freedom for Bangladesh“, which aims to inform the world about the political and social situation in the country.

“When the internet was cut, we started to organise in a group on Discord to exchange ideas about how we, who live abroad, could help our country.

We created the Facebook page ‘Freedom for Bangladesh’ to raise awareness about the situation in Bangladesh. There were people living in Australia, in the United States… young people all over the world were mobilising.”

‘It is not a matter of fear anymore’

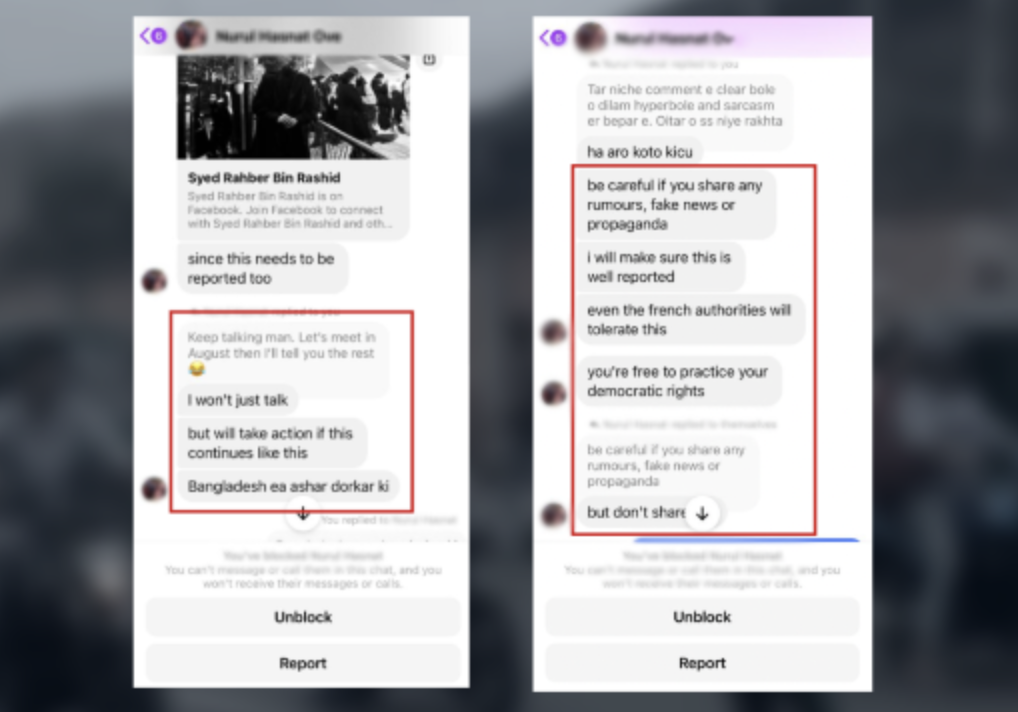

Rahber, who has lived in France for about a year, is no longer afraid to share his beliefs, thanks to his computer. However, he has faced threats from members of the Awami League, the party of former prime minister Sheikh Hasina.

“I have a lot of social media contacts who are part of the Awami League and who saw my work to raise awareness amongst the international community about what was happening in these protests.

Some of my ‘followers’ accused me of sharing false information and propaganda against Sheikh Hasina. There was even one member of the party who threatened to report me to the police, saying that he would “take action against me”.

This wasn’t a surprise to the young Bangladeshi. “It’s been like that for 15 years, many people have faced the same intimidation. Since we were children, we’ve had to think twice before criticizing anything. If I was still living in Bangladesh, someone definitely would have come and found me at home.”

Even though he is afraid that his activism might have repercussions for his family still in Bangladesh, Rahber wants to continue the fight. “Now that I’m in France, I have my freedom of expression,” he said. “It is not a matter of fear anymore.”